“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell just as sweet.” Delightful. This idea that a thing is the thing that it is, regardless of what we call it. That the inherent identity of an object far surpasses any linguistic limitations we can place on it. That its character will make itself known, nomenclature be damned! Shakespeare certainly wasn’t thinking about artists’ pigments when he wrote this.

The nomenclature of paints and pigments is so convoluted, it’s hard to know where to even begin. Let me start by establishing that a pigment is a single substance with a consistent chemical composition, whereas a paint may include one (or many) pigments mixed with an adhesive binder that cures into a paint film. Pigment(s) + Binder = Paint. The name on a tube of paint may or may not have any relevance whatsoever to the actual pigments in the paint. If it sounds like I’m being vague, I promise I’m just the messenger here.

Let’s take a look at Ultramarine Blue. This is a commonly known and used pigment that occurs naturally and is created synthetically. Below is a staggeringly ridiculous list of common, historic, and manufacturing names that have been given to Ultramarine Blue and the paints that are made from it:

This list of Ultramarine Blue names comes directly from a website detailing the Colour Index, or CI Generic Name.

First published in 1924, this system pins down pigments not by their ever-elusive common names, but rather by a specific codename that corresponds with the chemical composition of the pigment. The website Art is Creation looks pretty scammy, but is actually an incredibly thorough resource for accessing the Colour Index database– for free. I use this website all the time, and reference the CI name on any new paint or pigment before purchasing it.In this system, each code begins with two letters: P for pigment (always), Y for yellow, O for orange, R for red, V for violet, etc., depending on its general color. Then, there is a numerical value assigned. The number has to do with the arbitrary order in which the pigment was entered into the CI system, and has no relationship with when the pigment itself was discovered or invented. The key concept here is that the CI indicates the chemical composition, not the color. In fact, there can be a whole range of hues and values resulting from the same chemical composition.

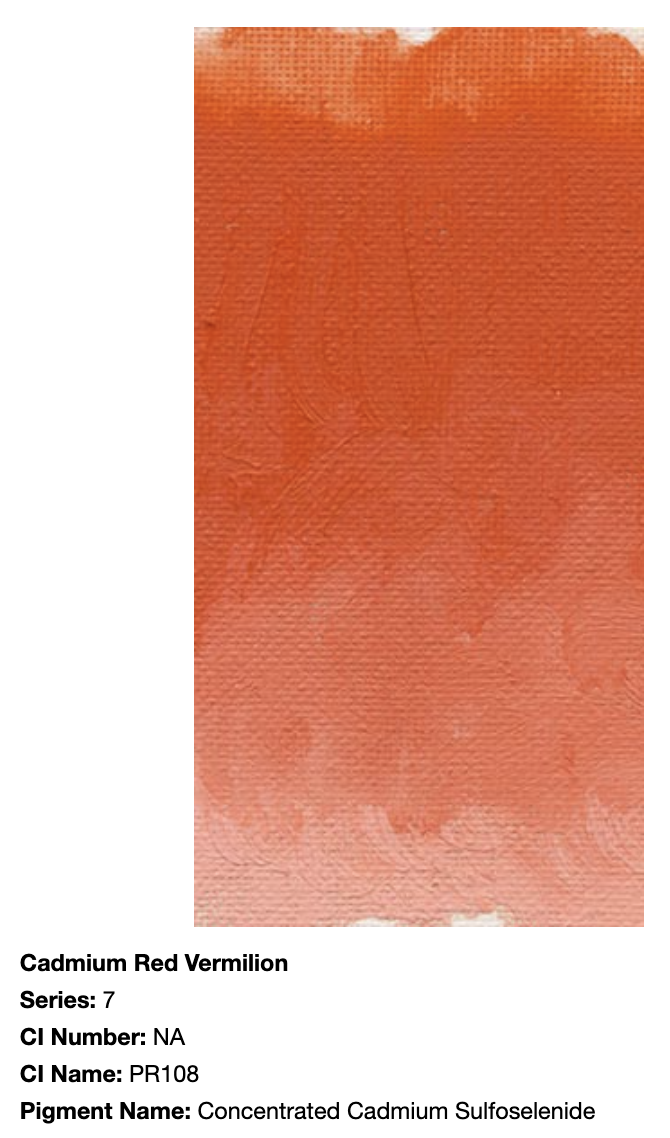

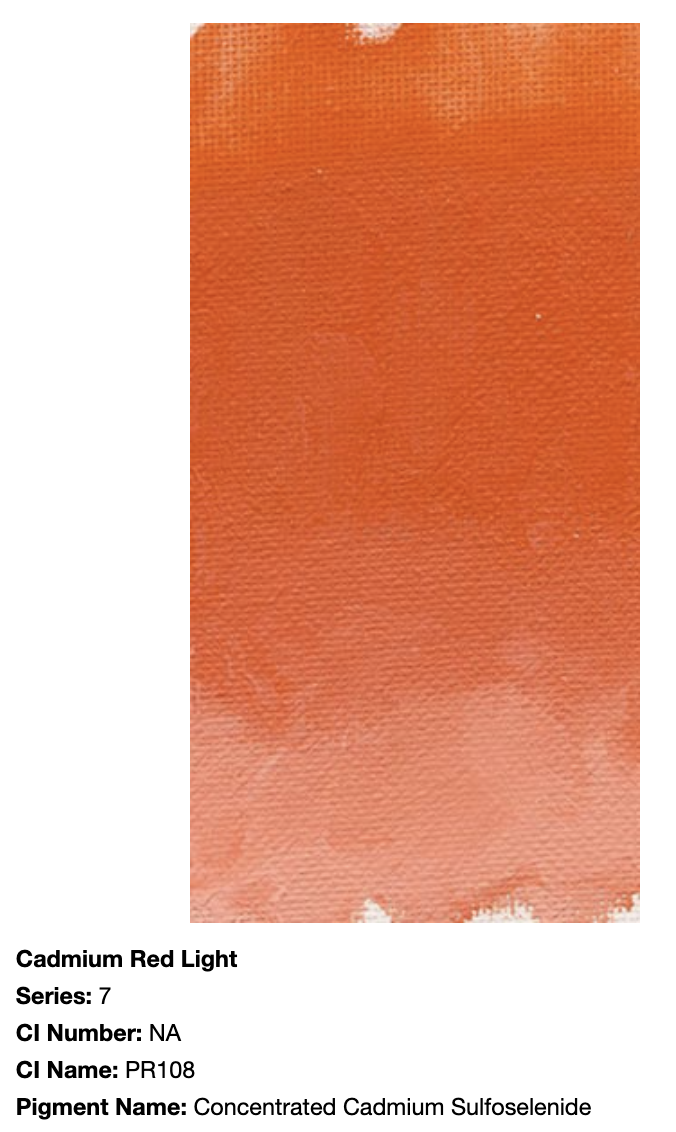

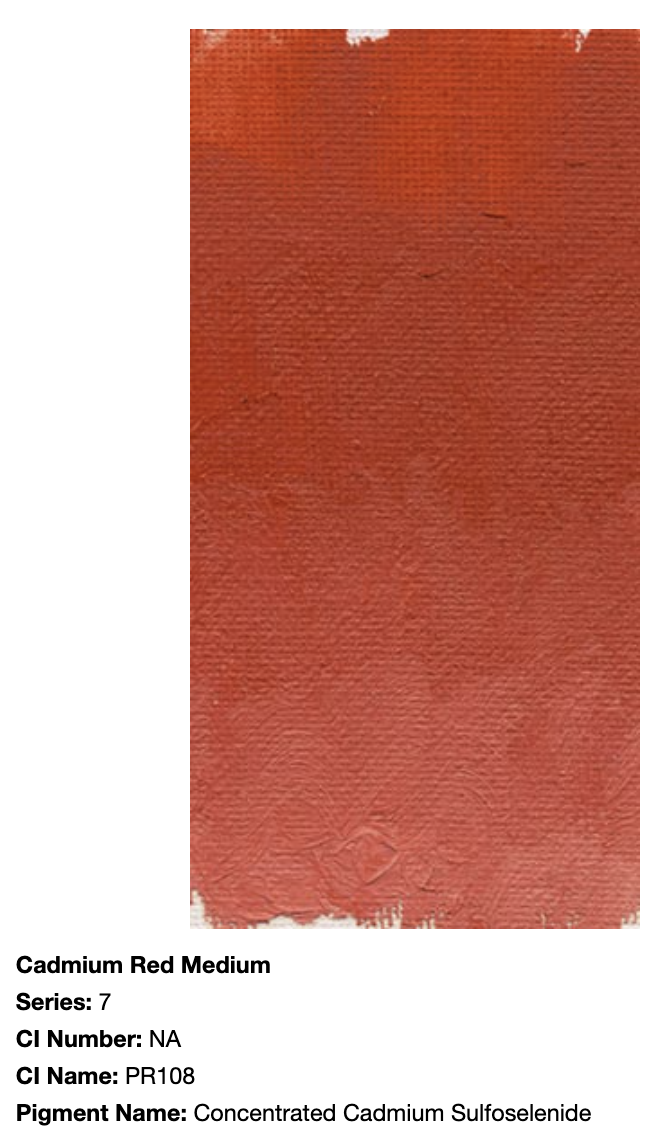

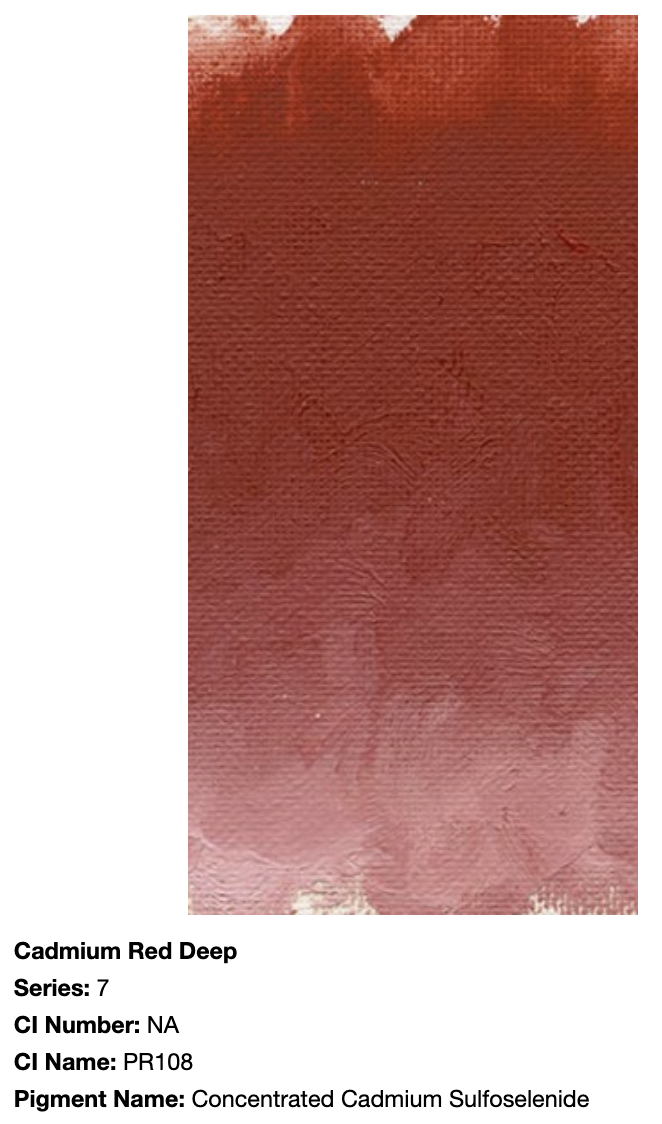

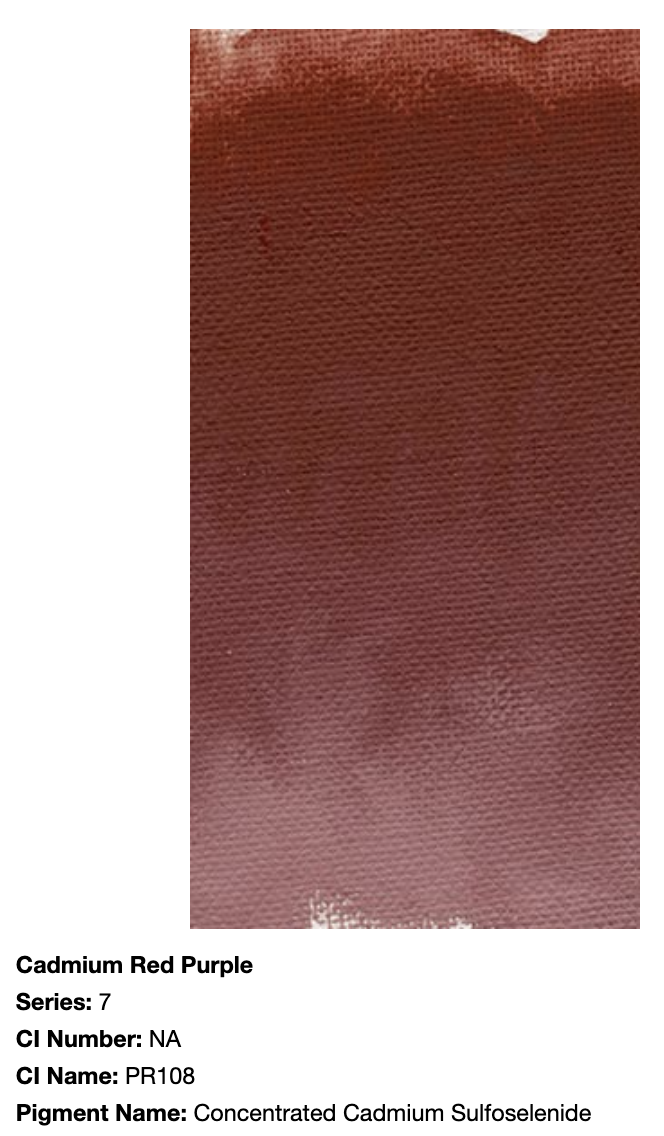

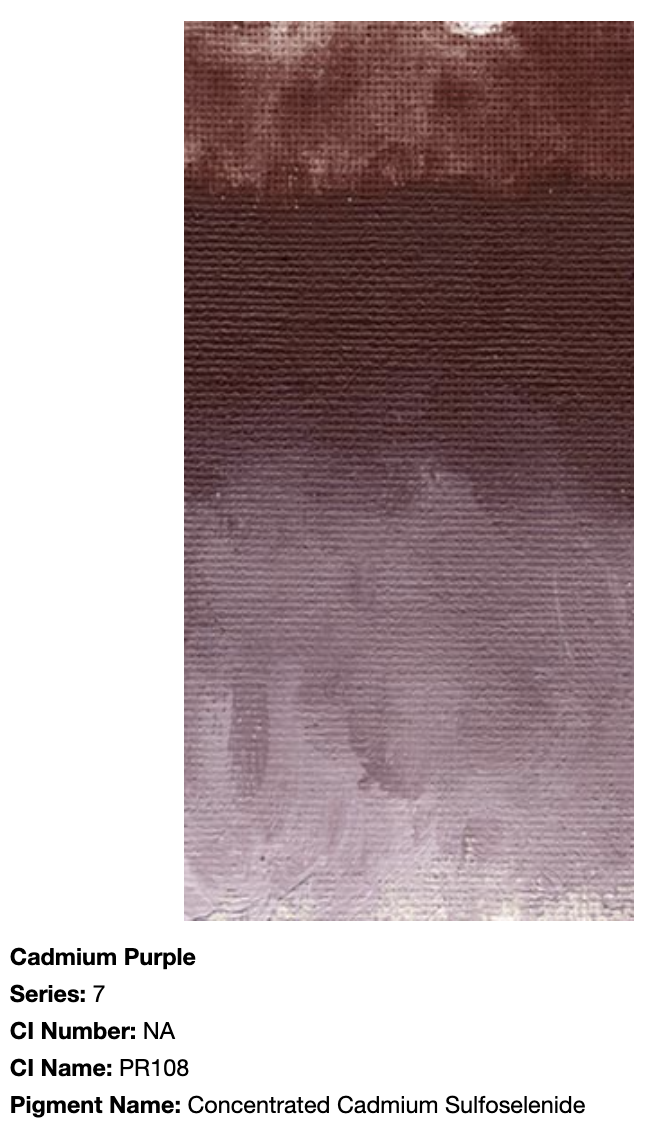

For example, PR108 is the CI Name for what we commonly know as Cadmium Red, chemically known as Cadmium Sulfoselenide. Williamsburg Oil Colors sells six different paints made from PR108 ranging from hot orange to deep purple.

While there is certainly some run-of-the-mill, modern-day industrial opacity at play on the surface of this nomenclature fiasco, underneath is a beautiful story about the unfolding of color origins across cultures and around the globe. Throughout time, pigments and paints have been named based on a variety of factors:

For their inventors: Scheele’s Green

Chemical derivation or composition: Cadmium Red, Cobalt Blue, Quinacridone Red, Chrome Yellow

Place of origin or invention: Turkey Brown, Ultramarine Blue, Verona Green Earth, Egyptian Blue

Port from which they have been shipped: Solferino

Use: Underpainting White, Portrait Pink

Resemblance to something else: Sky Blue, Lemon Yellow, Sap Green

The nomenclature of pigments can illuminate histories of place, culture, and how one material relates to another. Ultramarine comes from Latin ultra marinus meaning ‘beyond the sea,’ as it was brought to Europe from Afghanistan mainly by way of Venice. Vermillion comes from Latin vermis meaning ‘worm,’ as the intensity of the red evoked the natural red dye made from insects called Kermes vermilio. Graphite and black lead have long been confused because graphite has a similar metallic luster to galena, which is the mineral form of black lead sulfide. Additionally, graphite was historically known as plumbago, derived from the Latin word for ‘lead,’ plumbum. Think about how, to this day, we use graphite and lead interchangeably when we are talking about pencils. Shellac is a natural resin secreted from the lac insect, and also produces a red dye similar to cochineal. Shellac and lac are the linguistic roots of lake pigments, which are made by precipitating a soluble dye (such as cochineal) onto an inert inorganic particle. The images below are from the Material Archive of rare, historic, and natural painting materials that I created between 2018 and 2022:

A pigment will be what it already is regardless of what we call it. Whether we call it PBr7, Burnt Umber, or the iron on the surface of the earth that has literally lived thousands upon thousands more lifetimes than we will ever know. We can follow these lines of thinking, these modes of communicating, to trace the lives of our pigments through time and culture, to navigate the paint industry’s lack of transparency, and ultimately to figure out what the hell is inside the tubes of paint we’re using. Where the convolution of pigment nomenclature closes doors to immediate clarity, it opens other doors to a deeper understanding.